Astronomy

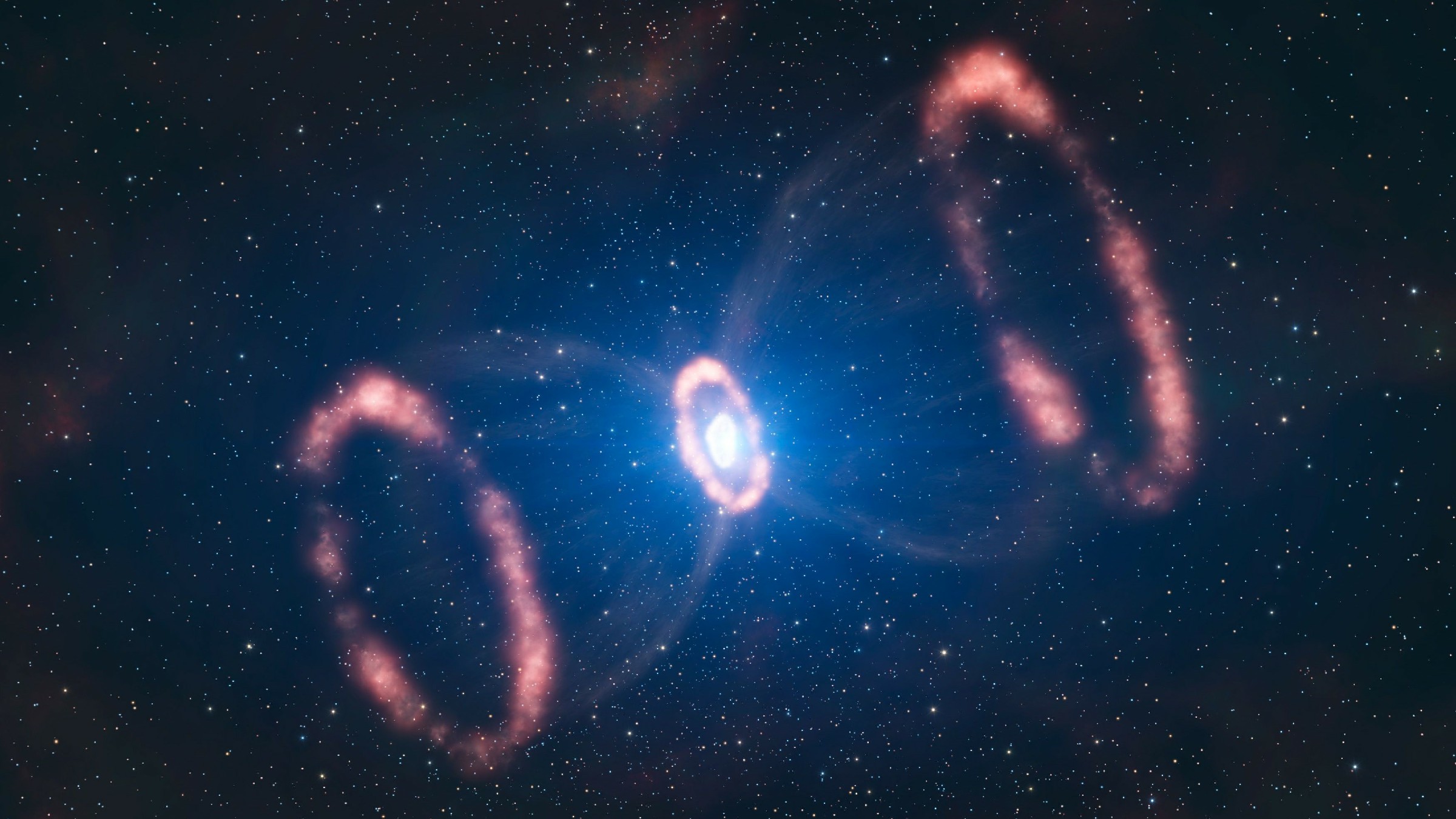

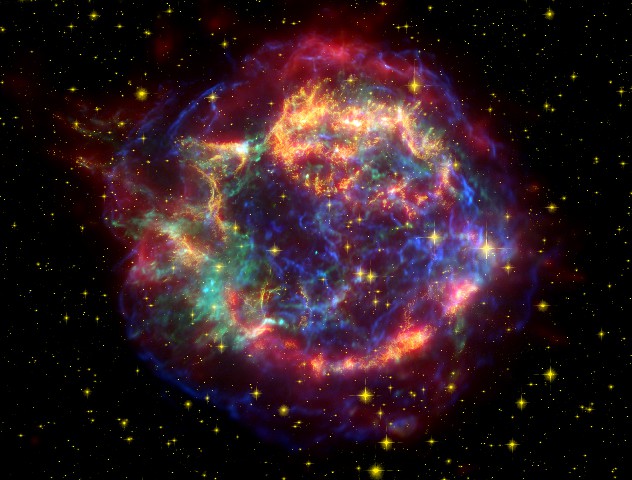

Neutron Stars

A neutron star is the collapsed core of a massive supergiant star, which had a total mass of between 10 and 25 solar masses, possibly more if the star was especially metal-rich. Neutron stars are the smallest and densest stellar objects, excluding black holes and hypothetical white holes, quark stars, and strange stars. Neutron stars have a radius on the order of 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) and a mass of about 1.4 solar masses. They result from the supernova explosion of a massive star, combined with gravitational collapse, that compresses the core past white dwarf star density to that of atomic nuclei.

Continue readingAstronomy

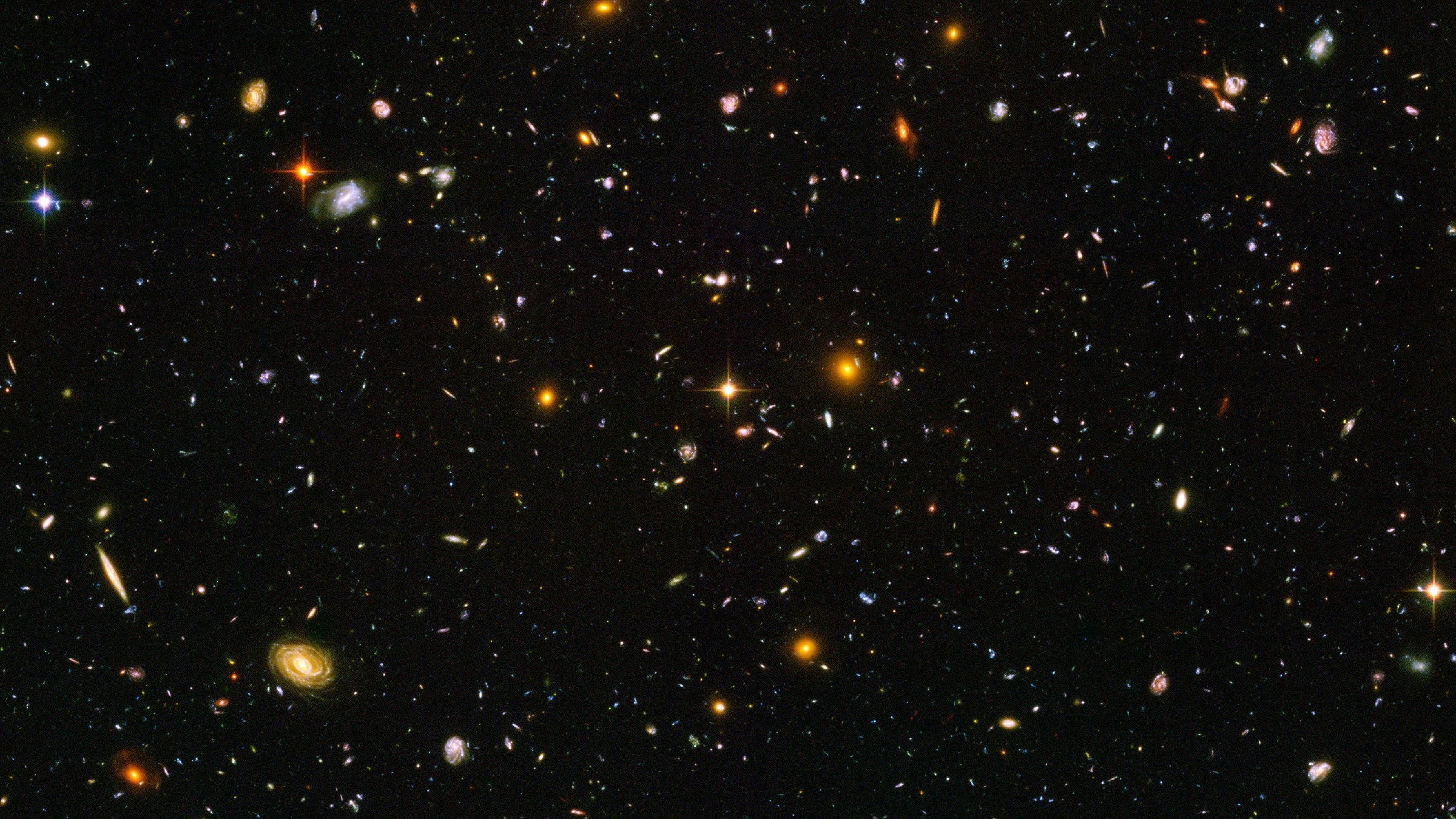

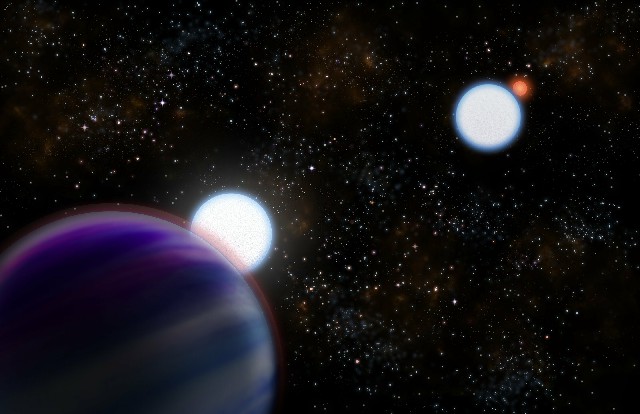

Exoplanets

An exoplanet or extrasolar planet is a planet outside the Solar System. The first possible evidence of an exoplanet was noted in 1917, but was not recognized as such. The first confirmation of detection occurred in 1992. This was followed by the confirmation of a different planet, originally detected in 1988. As of 1 December 2020, there are 4,379 confirmed exoplanets in 3,237 systems, with 717 systems having more than one planet.

Continue readingAstronomy

Quasars

A quasar (/ˈkweɪzɑːr/; also known as a quasi-stellar object, abbreviated QSO) is an extremely luminous active galactic nucleus (AGN), in which a supermassive black hole with mass ranging from millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun is surrounded by a gaseous accretion disk. As gas in the disk falls towards the black hole, energy is released in the form of electromagnetic radiation, which can be observed across the electromagnetic spectrum. The power radiated by quasars is enormous; the most powerful quasars have luminosities thousands of times greater than a galaxy such as the Milky Way. Usually, quasars are categorized as a subclass of the more general category of AGN. The redshifts of quasars are of cosmological origin.

Continue readingAstrophysics

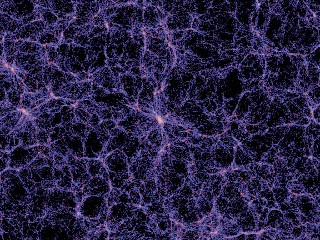

Dark Energy

In physical cosmology and astronomy, dark energy is an unknown form of energy that affects the universe on the largest scales. The first observational evidence for its existence came from supernovae measurements, which showed that the universe does not expand at a constant rate; rather, the expansion of the universe is accelerating.

Continue readingPhysics

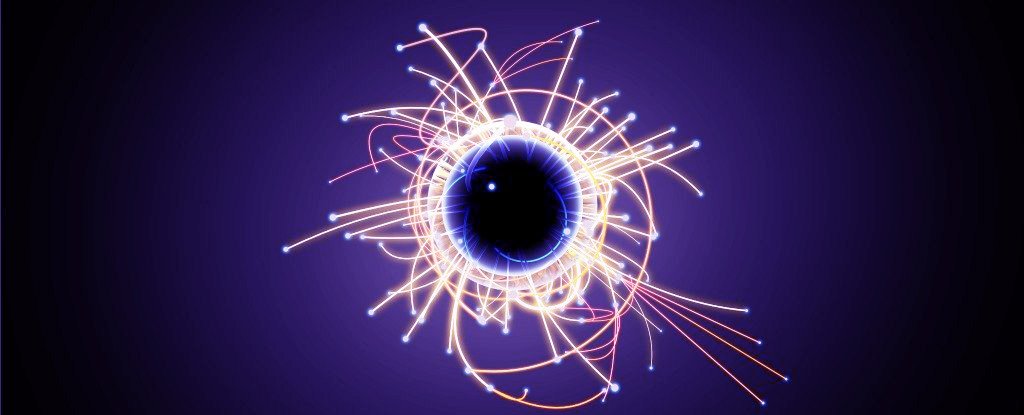

Higgs Boson

The Higgs boson is an elementary particle in the Standard Model of particle physics, produced by the quantum excitation of the Higgs field, one of the fields in particle physics theory. It is named after physicist Peter Higgs, who in 1964, along with five other scientists, proposed the Higgs mechanism to explain why some particles have mass. (Particles acquire mass in several ways, but a full explanation for all particles had been extremely difficult).

Continue readingPhysics

String Theory

In physics, string theory is a theoretical framework in which the point-like particles of particle physics are replaced by one-dimensional objects called strings. String theory describes how these strings propagate through space and interact with each other. On distance scales larger than the string scale, a string looks just like an ordinary particle, with its mass, charge, and other properties determined by the vibrational state of the string. In string theory, one of the many vibrational states of the string corresponds to the graviton, a quantum mechanical particle that carries gravitational force. Thus string theory is a theory of quantum gravity.

Continue reading